| |

|

|

| Herbert, George |

|

[ top ]

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

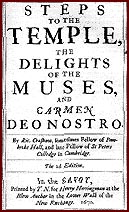

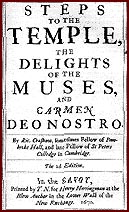

George

Herbert, as an eminent example among the "metaphysical

poets" of the 17th Century, was an Anglican pastor; when

George Herbert wrote "The Temple", England knew momentous

political, religious and social changes; it was a period of

transition discernible even in poetry. Herbert's pieces of poetry

display a quiet and sincere piety, although the poet is also

prone like Hopkins later to a pervasive religious realism which

finds its expression in the lyricism of his own inner torments.

Devotional verse might be so, at first, defined as such a sanctifying

fight which reveals that a personal encounter with God and a

personal experience of sin are concomitant. Herbert's willingness

to know himself better or to be closely akin to himself dictates

the very attitude of the poet towards love, death and God. In

Herbert's poetry, the soul takes refuge against the dread of

infinite space in the intimacy of the human heart, but instead

of being concentrated on the contemplation of some precious

object, the poet's mind is wide-open to the diversity of the

real and to all the adventures of man's wit. |

| |

|

|

|

The Altar

A broken ALTAR, Lord, thy servant

rears,

Made of a heart, and cemented with tears :

Whose parts are as thy hand did frame ;

No workman's tool hath touched the same.

A HEART alone

Is such a stone,

As nothing but

Thy pow'r doth cut.

Wherefore each part

Of my hard heart

Meets in this frame,

To praise thy Name :

That, if I chance to hold my peace,

These stones to praise thee may not cease.

O let thy blessed SACRIFICE be mine,

And sanctify this ALTAR to be thine.

|

|

L'autel

Ton serviteur, Seigneur, dresse un AUTEL

brisé,

Bâti d'un cœur et cimenté de larmes ;

Chaque partie est ce que ta main a créé ;

Nul outil d'ouvrier ne prit part à l'ouvrage.

Seul un CŒUR

Est une telle pierre,

Que rien sinon ta

Puissance ne taille ;

C'est pourquoi chaque partie

De ce cœur endurci

En vient en ce corps

A louer ton nom :

Que, s'il m'arrive de m'abstenir de parler,

Ces pierres puissent ne cesser de te glorifier.

Oh fasse que ton bienheureux SACRIFICE soit mien,

Et sanctifie cet AUTEL afin qu'il soit tien.

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| Hopkins, Gerard Manley |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Gerard Manley Hopkins, as a

19th-century poet, converted in his youth to "the religion

of the Real Presence", recapitulated the features of

the preceding religious poets and heralded modern poetry.

Hopkins' precocious and artistically sensitive disposition,

encouraged by the family who bred him, was nourished by a

constant interest and a critical curiosity about the poets

who preceded or accompanied him throughout the Victorian period;

to his friend and privileged reader, Robert Bridges, at a

time when Hopkins' poetry seemed too obscure to the Poet Laureate,

the Jesuit Father said that he would orient his literary works

to the understanding of future generations. The fact that

his poems, by courtesy of Bridges who published them, have

found an audience only nearly thirty years after his death

would prove it, in a way. As important as the posthumous publications

of his work, Hopkins' conversion to Catholicism is unavoidable

if we want to understand the quite revolutionary dimension

of the poet. Like Herbert, the parson, Hopkins considered

his priesthood in the Company of Jesus as the first and maybe

last thing that did matter in his life; he dedicated his poetry

entirely to the glory of God.

|

| |

|

|

| The last sonnets of Hopkins show

an extraordinary lucidity about his own life; as if aware of

his near death, he writes his sonnets of desolation like a kind

of testament which keeps the marks of a man who suffered a lot

from loneliness. His faith in God seems to be mostly marred

but, far from him is the idea of apostasy. God's presence is

throughout Hopkins' literary work perceived and experimented

by a constant use of his reason, the discursive reason of the

clear-sighted analyst he was, an element which should prevent

us to define him as a mystic. There is no doubt that Hopkins

may now appear anachronistic as a person and priest; though

very proud of his country, as a matter of fact, the poet belonged

to the times of greater changes and the irresistible whirlwind

of his inner struggles heralded the feeling of absurdity which

would reign in the first decades of the century shaken by the

two first World Wars. Hopkins' message can do nothing but give

way to a new impetus of Christianity in a form that challenges

the classical methods of writing, by granting greater importance

to "orality" and to the call of poetry licences that

modern poetry fully adopted. To draw a last parallel between

Herbert, Hopkins and Blake introduced as my favourites poets,

I would say that Blake wanted to re-define religion, the sense

of God and His action in the world whereas Hopkins as well as

Herbert wanted to re-create God's action in the world in order

to reinforce the sense of His presence. |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

Thou

art indeed just, Lord, If I contend

With thee; but, sir, so what I plead is just.

Why do sinners' ways prosper? and why must

Disappointment all I endeavour end?

Wert thou my enemy, O

thou my friend,

How wouldst thou worse, I wonder, than thou dost

Defeat, thwart me? Oh, the sots and thralls of lust

Do in spare hours more thrive than I that spend,

Sir, life upon thy cause.

See, banks and brakes

Now, leavéd how thick! lacéd they are again

With fretty chervil, look, and fresh wind shakes

Them; birds build - but

not I build; no, but strain,

Time's eunuch, and not breed one work that wakes.

Mine, O thou lord of life, send my roots rain.

March 17, 1889

|

|

Oui, juste es-tu, Seigneur,

si je dispute avec

Toi; mais, ô maître, aussi juste est mon plaidoyer.

Pourquoi prospèrent-elles les voies des pécheurs?

Et

Pourquoi toutes mes tentatives finissent par l'échec?

Serais-tu mon ennemi,

toi qui es mon ami,

Comment ferais-tu pire, je me demande, sinon

Par revers et traverses? Oh, l'ivre esclave du vice

Avance plus à ses heures perdues que moi, ô mon

Maître, qui use

ma vie pour ta cause. Vois les rives

Foisonnent d'épais halliers! leurs festons revenus

De cerfeuil frisé, regarde, le vent frais les rive

Au sol; les oiseaux bâtissent

leurs nids, mais moi, nul

Nid, mais force, eunuque du temps, engendre nulle oeuvre vive.

Mien, toi Dieu de vie, donne aux racines miennes tes nues.

|

| |

|

|

| Goethe, Johann Wolfgang

v. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Please

listen to Brahms, who set these three stanzas only into music,

and hear how Goethe's despair has been well rendered! Together

with his German Requiem and a Rhapsody with Hölderlin's

Fate song, Brahms let us imagine how Goethe reached, during

this lonely trip in the mountains of Harz, a certain level of

mysticism. May the poet's prayer be our prayer! |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

Harzreise im Winter

Dem Geier gleich (...), schwebe mein Lied!

(...)

Aber abseits wer ist's?

Ins Gebüsch verliert sich sein Pfad,

Hinter ihm schlagen

Die Sträucher zusammen,

Das Gras steht wieder auf,

Die Öde verschlingt ihn.

Ach, wer heilet die Schmerzen

Des, dem Balsam zu Gift ward?

Der sich Menschenhass

Aus der Fülle der Liebe trank!

Erst verachtet, nun ein Verächter,

Zehrt er heimlich auf

Seinen eigen Wert

In ungnügender Selbstsucht.

Ist auf deinem Psalter,

Vater der Liebe, ein Ton

Seinem Ohre vernehmlich,

So erquicke sein Herz!

Öffne den umwölkten Blick

Über die tausend Quellen

Neben dem Durstenden

In der Wüste!

|

|

Le voyage du Harz en hiver

Pareil au vautour (...), plane mon chant!

(...)

Mais qui se tient là à l'écart ?

Dans les broussailles se perd son sentier,

Derrière lui

Les buissons se referment,

L'herbe relève ses tiges,

La désolation l'engloutit.

Ah, qui peut guérir

les souffrances

De celui pour qui le baume fut poison,

Ayant bu la haine des hommes

Dans la plénitude de l'amour ?

D'abord trahi, le voici traître à son tour,

Qui consume en secret

Sa propre valeur

En un égoïsme inassouvi.

S'il y a sur ta harpe,

Père d'amour, un accord

Sensible à son oreille,

Console son cœur !

Dévoile au regard embrumé

Les mille sources

Près de l'être assoiffé

Dans le désert !

|

|

| |

|

|

| Blake, William |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

In

advance of what the Industrial Revolution presented as signs

of apocalyptic collapse, such as the gradual rural migration

towards the ghettoes of the new cities and the pauperization

of the urban districts of the working-class, Blake turned his

eyes towards the poor and the outcast; as a poet, he "chanted"

the sanctity of home and the sweetness of childhood; In the

Songs of Innocence, we can guess the original state of the soul;

an image of that perfect condition of being is, according to

William Blake, the condition of childhood, in which a state

of happiness, unity and enjoyment always prevails, even among

some pangs and pains, for a child can and usually does vent

his spleen on an adult. In the Songs of Experience, the soul

has eaten the Forbidden Fruit from the Tree of Knowledge; all

the previous states described in the heaven of innocence are

now destroyed and become as many hells of experience, a condition

presaging disillusion, cruelty and death. From the Songs of

Innocence to the image of a bride-like city descending upon

earth when called by the Spirit, Blake chose the Incarnation

as a main theme of his poetry; but the Incarnation on Blake's

lips rather means the tragic feeling of life. |

|

| |

|

|

|

The Lamb

Little Lamb, who made thee ?

Dost thou know who made thee ?

Gave thee life, and bid thee feed,

By the stream and o'er the mead ;

Gave thee clothing of delight,

Softest clothing, wooly, bright ;

Gave thee such a tender voice,

Making all the vales rejoice ?

Little Lamb, who made thee ?

Dost thou know who made thee ?

Little Lamb, I'll tell thee,

Little Lamb, I'll tell thee :

He is calléd by thy name,

For He calls himself a Lamb.

He is meek, He is mild ;

He became a little child.

I a child, and thou a Lamb,

We are calléd by His name.

Little Lamb, God bless thee !

Little Lamb, God bless thee !

1789, Songs of Innocence

|

|

L'agneau

Petit Agneau, qui t'a créé

?

Sais-tu seulement qui t'a fait,

Donné de naître et vivre et paître,

Au bord de l'eau et sur le pré;

Donné de revêtir délices

Et douceur de laine et lumière;

Donné de vibrer d'une tendre voix,

Jusqu'à combler de joie tout val ?

Petit Agneau, qui t'a créé ?

Sais-tu seulement qui t'a fait ?

Petit Agneau, tu vas l'entendre,

Petit Agneau, tu vas l'entendre:

De ton nom, il est appelé,

Car Lui-même s'est dit Agnelet.

Il est humble et doux, tout autant;

Et Il se fit petit enfant.

Et moi, l'enfant, et toi, l'agneau,

Nous sommes appelés de Son nom.

Petit Agneau, Dieu te bénisse !

Petit Agneau, Dieu te bénisse !

1789, Chants d'Innocence

|

| |

|

|

| Crashaw, Richard |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

As a European literary movement, Metaphysical Poetry also derives from a philosophical background based on the concept of « teatra mundi » ; whereas drama is,

according the high baroque poet, understood in terms of spectacle, it is, according to the metaphysical poet, rather treated as essence. At any rate, England knew momentous political, religious and social changes.Crashaw

himself belonged, like Donne also and later Hopkins, to the

numerous poets who experimented in their own life a conversion.

But more important than the confession itself, which everyone

chose, is according to me the way which brought to such a vision

of the world. For Crashaw, this spiritual way had also something

to do with journeys and stays throughout Europe, as if the search

of God, the unique God, was only a better way of being acquainted

with man's versatile nature, at last, or vice-versa.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Upon Our Saviour's Tomb

Wherein Never Man Was Laid

How Life and Death in thee

Agree !

Thou had'st a virgin Womb

And Tomb.

A Joseph did betroth

Them both.

|

|

Sur la Tombe de Notre

Sauveur

Où Jamais Homme ne Fut Déposé

Oh, que ne sont-elles en Toi, la Vie et la Mort,

D'accord !

Vierges te sont le Sein de ta mère et, au comble,

Ta Tombe.

Un Joseph les choisit pour objet de ses voeux

Tous deux.

|

| |

|

|

| Trakl, Georg |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

One

of the peculiarities of Trakl's poems is the presence of autumn

landscapes at the countryside and the hope of a mystical sense

of life. The beauty of nature with its calming rhythm of cycles

however fails, where gruesome death comes up in daily life.

Be it an aspect of Expressionism or not, this fascination of

madness and of the impossible in Trakl's poetry reminds us of

his personal experience of horror at the beginning of World

War One, as he had to nurse a lot of injured and did not succeed

in looking at so much suffering. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Der Herbst des Einsamen

Der dunkle Herbst kehrt ein voll Frucht und Fülle,

Vergilbter Glanz von schönen Sommertagen.

Ein reines Blau tritt aus verfallener Hülle;

Der Flug der Vögel tönt von alten Sagen.

Gekeltert ist der Wein, die milde Stille

Erfüllt von leiser Antwort dunkler Fragen.

Und hier und dort ein Kreuz auf ödem

Hügel;

Im roten Wald verliert sich eine Herde.

Die Wolke wandert übern Weiherspiegel;

Es ruht des Landmans ruhige Gebärde.

Sehr leise rührt des Abends blauer Flügel

Ein Dach von dürrem Stroh, die schwarze Erde.

Bald nisten Sterne in des Müden

Brauen;

In kühle Stuben kehrt ein still Bescheiden

Und Engel treten leise aus den blauen

Augen der Liebenden, die sanfter leiden.

Es rauscht das Rohr; anfällt ein knöchern Grauen,

Wenn schwarz der Tau tropft von den kahlen Weiden.

|

|

L'automne du solitaire

L'automne obscur revient, des fruits à profusion,

Splendeur toute jaunie des belles journées d'été.

Un bleu pur sort des feuilles tombées de la foison;

Le vol d'oiseaux résonne de légendes éloignées.

Le vin est mis en cave, et à d'obscures questions,

Le doux silence répond rempli de bruits légers.

Et çà et là

une croix sur une colline déserte;

Dans une forêt pourpre, un troupeau vient se perdre.

Le nuage chemine, miroité dans l'étang;

Cela calme le geste calme du paysan.

Presque sans aucun bruit, l'aile bleue du soir frôle

Un toit de chaume sec, la terre noire au sol.

Bientôt, des étoiles nichent aux sourcils

des suées;

Un homme, modeste et calme, balaye de frais préaux

Et des anges quittent sans bruit les yeux bleus des amants,

Lesquels souffrent un peu plus soulagés maintenant.

Le roseau bruisse au vent; surgit l'horreur des os

Quand, noire, la rosée tombe des pâturages pelés.

|

|